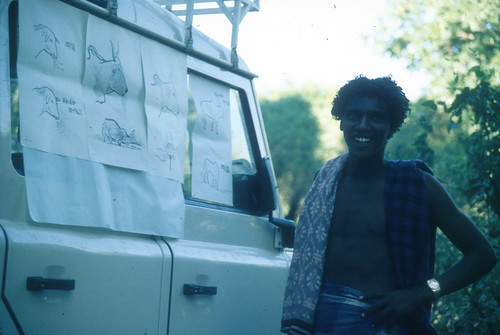

In a new analysis in Science, ILRI researcher Jeffrey Mariner describes how the world eradicated deadliest cattle plague, the second such success after smallpox. The authors of the paper reveal the essential role of Africa’s nomadic herders in ridding the world of rinderpest. Above, an Afar community animal health worker in 1993 describes the appearance and characteristics of rinderpest in cattle (photo by Jeff Mariner).

A new analysis published today in Science traces the recent global eradication of the deadliest of cattle diseases, crediting not only the development of a new, heat-resistant vaccine, but also the insight of local African herders, who guided scientists in deciding which animals to immunize and when. The study provides new insights into how the successful battle against rinderpest in Africa, the last stronghold of the disease, might be applied to similar diseases that today ravage the livestock populations on which the livelihoods of one billion of the world’s poor depend.

Capable of wiping out a family’s cattle in just a few days, rinderpest was declared vanquished in May 2011. After smallpox, it is only the second disease (and first livestock disease) ever to be eradicated from the earth.

‘The elimination of rinderpest is an enormous triumph against a disease that has plagued animals and humankind for centuries’, said Jimmy Smith, director general of the International Livestock Research Institute (ILRI). ‘Science succeeded despite limited resources, and we now know how. We are committed to applying the lessons in this study to making progress against other similarly destructive livestock diseases.’

According to the analysis, which was conducted by international scientists coordinated by ILRI, and published this week in Science, the eradication of rinderpest happened thanks to the development of an effective temperature-stable vaccine, collaborations between veterinary health officials and cattle farmers to deliver those vaccines, and reliance on the knowledge and expertise of the local herders to determine the location and movement of outbreaks.

The cattle plague and its path of destruction

Rinderpest, known as ‘cattle plague’ in English, is thought to have had its origin in the dense cattle herds of Central Eurasia more than two millennia ago and subsequently spread through warfare and trade to cattle in Europe, Asia and eventually Africa. Caused by a virus related to the one that causes measles and canine distemper, rinderpest could infect cows, water buffalos and other cloven-hoofed animals, leading to a high fever, severe diarrhea, then dehydration and emaciation. The pathogen could kill 90 per cent of a herd, wiping out an entire farm’s livestock in just a matter of days. There was no treatment.

While rinderpest is not dangerous to human health, its impact on humanity has been significant. Its path of destruction has been linked to many history-changing events such as the fall of the Roman Empire, the French Revolution and famines throughout Africa since the 19th century. Indeed, nearly three-quarters of the rural poor and some one-third of the urban poor depend on livestock for their food, income, traction, manure or other services. Livestock provide poor households with up to half their income and between 6 and 35 per cent of their protein consumption. The loss of a single milking animal can affect a family’s economic health, while depriving it of a primary source of nutrition.

Road to eradication

The first major contributing factor to eradication, as identified by the analysis, was a major improvement made to an existing rinderpest vaccine. While the original vaccine was safe, effective, affordable, and easy to produce, it needed to be refrigerated—making it nearly impossible to transport it to remote rural villages. With the development of a new heat-resistant vaccine formulation in 1990 that could be stored at 37 °C for eight months, and in the field without refrigeration for 30 days, scientists had a tool that would become the cornerstone of the eradication effort in remote pastoral areas of Africa.

But according to ILRI’s Jeffrey Mariner, the analysis’ lead author and inventor of the temperature-stable rinderpest vaccine, it was the role played by pastoralists that really turned rinderpest on its head.

As part of a public-private-community partnership, Mariner and colleagues trained what they called community-based animal health workers, or CAHWs—local pastoralists who were willing to travel on foot and able to work in remote areas—on how to deliver the new vaccine. These CAHWs carried the vaccine from herd to herd, immunizing all the cattle in their communities.

The local herders performed as well, if not better, than did veterinarians at vaccinating the herds—in fact often achieving higher than 80 per cent herd immunity in a short time—remarkable for a disease that had plagued most of the world for millennia. Indeed, it turned out that the pastoralists were not only very, very good at delivering the vaccine, but that they also knew more about the disease and how to stop it than many of the experts.

‘We soon discovered that the livestock owners knew more than anyone—including government officials, researchers or veterinarians—where outbreaks were occurring’, Mariner said. ‘It was their expertise about the sizes of cattle herds, their location, seasonal movement patterns and optimal time for vaccination that made it possible for us to eradicate rinderpest.’

Based on their immense expertise about migratory patterns and in recognizing early signs of infection, the herders were able to pinpoint, well before scientists ever could, where some of the final outbreaks were occurring—often where conventional surveillance activities had failed to disclose disease. Harnessing this knowledge of rinderpest through ‘participatory surveillance’ of outbreaks to CAHW delivery of vaccination proved to be the most successful approach to monitoring and controlling the disease. It effectively removed the disease from some of the hardest-to-reach, but also most disease-ridden, communities.

Applying rinderpest lessons to other diseases

While livestock and those who depend on them for food, transportation and economic stability are now safe from one major pathogen, they continue to be plagued by a number of other dangerous and debilitating diseases—some as deadly as rinderpest.

The international animal health community is now gearing up to address the next major constraint to livestock livelihoods in Africa and Asia. In their analysis, Mariner and colleagues consider how the lessons learned from battling rinderpest can be applied to protect livestock from other infectious agents—particularly peste des petits ruminants (PPR), also known as ‘goat plague’. Strategies to address PPR using the lessons from rinderpest have been developed and action is under way to mobilize international support for a coordinated program to tackle PPR. As a next step, ILRI and the Africa Union/Interafrican Bureau for Animal Resources are planning to host the next meeting of the PPR Alliance, a partnership of research and development organizations who prioritize PPR, in Nairobi in early 2013.

A dangerous virus that can destroy whole flocks of sheep and goats, PPR threatens livestock owners in Africa, Asia and the Middle East, in particular. As with rinderpest, a sheep or goat infected with PPR will come down with a high fever and will stop eating, leading to severe diarrhea and death. Eventually, it will take down the entire herd of the animals, which are equal to cattle in their importance to the poor. And controlling PPR is made challenging by the short life span and heavy trading of sheep and goats—making it difficult to keep the disease in check and preventing its spread to new areas.

Nonetheless, the lessons of rinderpest eradication have begun to have an impact on the toll exacted by goat plague. Participatory surveillance methods are now applied in many countries, CAHWs are now frequently involved in vaccination campaigns and ILRI has developed a temperature-stable vaccine that can be transported to rural farms and has started to put into place training programs for shepherds and farmers in Uganda and Sudan to deliver it.

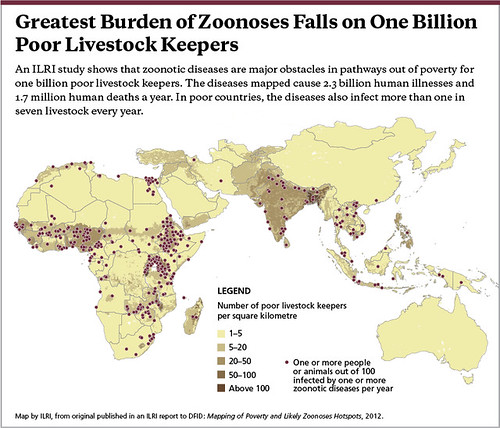

Eventually, these same lessons could be applied to other livestock diseases such as foot-and-mouth disease—even some that have recently jumped to humans, like avian flu. Such ‘zoonotic’ diseases are responsible for 2.4 billion cases of human illness and 2.2 million deaths per year, primarily in low- and middle-income countries.

Read the paper in Science (subscription required to read full text): Rinderpest eradication: Appropriate technology and social innovations, by Jeffrey Mariner, James House, Charles Mebus, Albert Sollod, Dickens Chibeu, Bryony Jones, Peter Roeder, Berhanu Admassu, Gijs van ’t Klooster, 14 September 2012, Vol. 337 no. 6100 pp. 1309–1312, DOI: 10.1126/science.1223805.

Read previous articles on this blog about the eradication of rinderpest: Goat plague next target of veterinary authorities now that cattle plague has been eradicated, 4 Jul 2011.

Deadly rinderpest virus today declared eradicated from the earth–’greatest achievement in veterinary medicine’, 28 Jun 2011.

Why technical breakthroughs matter: They helped drive a cattle plague to extinction, 28 Oct 2010.

Today, ILRI Director General Jimmy Smith expressed his great appreciation to the many people who contributed feedback and ideas for a new ILRI strategy.

Today, ILRI Director General Jimmy Smith expressed his great appreciation to the many people who contributed feedback and ideas for a new ILRI strategy.