Territory size shows the proportion of worldwide meat consumption that occurs there (map by Worldmapper). Meat consumption per person is highest in Western Europe, with nine of the top ten meat-consuming populations living in Western Europe (the tenth in this ranking is New Zealand). The most meat is consumed in China, where a fifth of the world population lives.

Authors of a new paper setting out the roles of livestock in developing countries argue that although providing a ‘balanced account’ of livestock’s roles entails something of a ‘balancing act’, we had better get on with it if we want to build global food, economic and environmental security.

‘The importance of this paper lies in providing a balanced account [for] . . . the often, ill-informed or generalized discussion on the . . . roles of livestock. Only by understanding the nuances in these roles will we be able to design more sustainable solutions for the sector.

‘We are at a moment in time where our actions could be decisive for the resilience of the world food system, the environment and a billion poor people in the developing world . . . . At the same time, . . . the demand for livestock products is increasing, . . . adding additional pressures on the world natural resources.

Not surprisingly, the world is asking a big question: what should we do about livestock?

The paper, by scientists at the International Livestock Research Institute (ILRI), provides ‘a sophisticated and disaggregated answer’.

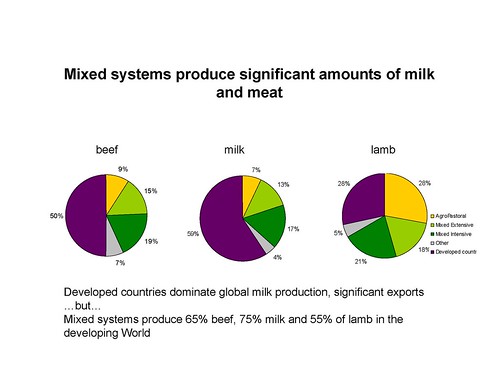

‘The sector is large. There are 17 billion animals in the world eating, excreting and using substantial amounts of natural resources, mostly in the developing world, where most of the growth of the sector will occur. The roles of livestock in the developing world are many . . . . [L]ivestock can be polluters in one place, whereas in another they provide vital nutrients for supporting crop production.’

The picture is complex. Whether for its positive or negative roles, livestock are in the spotlight. . . . [M]aking broad generalizations about the livestock sector [is] useless (and dangerous) for informing the current global debates on food security and the environment.

So what are these ‘nuanced, scientifically informed messages about livestock’s roles’ that the authors say are essential? Well, here are a few, but it is recommended that interested readers read the paper itself to get a sense of the whole, complicated, picture.

In a nutshell (taken from the paper’s conclusion), the authors say that ‘weighing the roles that livestock play in the developing world’ is a ‘complex balancing act’.

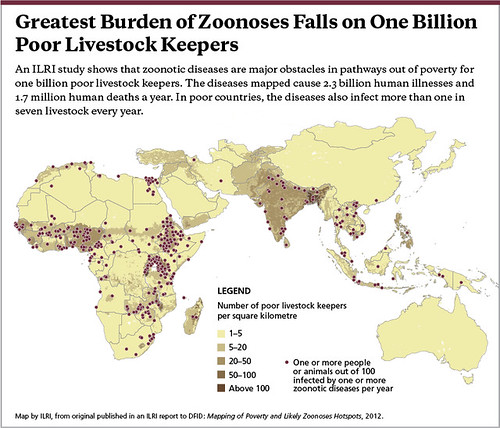

On the one hand, we acknowledge that livestock is an important contributor to the economies of developing nations, to the incomes and livelihoods of millions of poor and vulnerable producers and consumers, and it is an important source of nourishment. On the other side of the equation, the sector [is a] . . . large user of land and water, [a] notorious GHG [greenhouse gas] emitter, a reservoir of disease, [and a] source of nutrients at times, polluter at others . . . .

‘Against this dichotomy, [this] is a sector that could improve its environmental performance significantly . . . .’

This paper argues that we will help ensure poor decision-making in the livestock sector if we do the following.

Continue to ignore the inequities inherent

in the debate on whether or not to eat meat

‘This debate translates into poor food choices v. the food choices of the poor [and remains] dominated by the concerns of the developed world, [whose over-consumers of livestock and other foods] . . . should reduce the consumption of animal products as a health measure. However, the debate needs to increase in sophistication so that the poor and undernourished are not the victims of generalisations that may translate into policies or reduced support for the livestock sector in parts of the world where the multiple benefits of livestock outweigh the problems it causes.’

Take as given the projected trajectories of animal

consumption proposed by the ‘livestock revolution’

These trajectories ‘are not inevitable. Part of our responsibility is to challenge these future trajectories, and ensure that we identify levels of consumption and nutritional diversity for different parts of the world that will achieve the best compromise between a healthy diet that includes livestock products (or not), economic growth, livelihoods and livestock’s impacts on the environment. No mean feat, but certainly a crucial area of research.’

Continue to promote large-scale consolidated farms over efficient

and market-oriented smallholders as engines for feeding the world

‘Advocates of large-scale farming argue in favour of the higher efficiencies of resource use often found in these systems and how simple it is to disseminate technology and effect technological change. True, when the market economy is working.’ Not true when the market economy is not working. Investment in developing efficient value chains is essential ‘to create incentives for smallholders to integrate in the market economy, formal or informal.’

Continue to hurt the competitiveness

of the smallholder livestock sector

‘Formal and informal markets will need to ensure the supply of cheaper, locally produced, safe livestock products to adequately compete. This implies a significant reduction in transaction costs for the provision of inputs, increased resource use efficiencies, and very responsive, innovative and supporting institutions for the livestock sector in developing countries (FAO, 2009).

Continue to give lip service to paying for environmental services—

and continue to ignore livestock keepers as targets of these services

‘Proofs of concept that test how these schemes could operate in very fragmented systems, with multiple users of the land or in communal pastoral areas, are necessary. Research on fair, equitable and robust monitoring and evaluation frameworks and mechanisms for effecting payments schemes that work under these conditions is necessary. The promise of PES [payment for environmental services] schemes as a means to . . . produce food while protecting the world’s ecosystems is yet to be seen on a large scale.’

Don’t help small-scale livestock farmers and herders

adapt to climate change or help mitigate global warming

In a low carbon economy, and as the global food system prepares to become part of the climate change negotiations, ‘it will be essential that the livestock sector mitigate GHG [greenhouse gas emissions] effectively in relation to other sectors. Demonstrating that these options are real, with tangible examples, is essential . . . .’

Don’t modify institutions and markets to reach smallholders—

and continue to ignore women livestock producers

‘Underinvestment in extension systems and other support services has rendered poor producers disenfranchised to access support systems necessary for increasing productivity and efficiency’ or safety nets. Increased public investment in innovation and support platforms to link the poor, and especially women, to markets is essential.

Continue to protect global environmental goods

at the expense of local livelihoods of the poor

‘. . . [S]tern public opinion in favour of protecting global environmental goods, instead of local livelihoods, could create an investment climate’ that hurts smallholder farmers. The informal and formal retail sectors must ‘gain consumers trust as safe providers of livestock products for urban and rural consumers’.

Bottom line: Need for nuanced information / narratives / approaches

The authors conclude their paper with a plea for greater tolerance for ambiguity and diversity rather than fixed ideas, and a greater appetite for accurate and location-specific information rather than simplistic generalities.

Balancing the multiple roles of livestock in the developing world and contrasting them with those in the developed world is not simple.

‘The disaggregated evidence by region, species, production system, value chain, etc. needs to be generated. Messages need to be well distilled, backed by scientific evidence and well articulated to avoid making generalisations that more often than not confuse the picture and ill-inform policy. Livestock’s roles are simply not the same everywhere.

The roles, whether good or bad, need to be accepted by the scientific community.

‘Research agendas need to use the livestock bads as opportunities for improvement, while continuing to foster the positive aspects. These are essential ingredients for society to make better-informed choices about the future roles of livestock in sustainable food production, economic growth and poverty alleviation.’

Access the full paper

The roles of livestock in developing countries, by ILRI authors Mario Herrero, Delia Grace, Jemimah Njuki, Nancy Johnson, Dolapo Enahoro, Silvi Silvestri and Mariana Rufino, Animal (2013), 7:s1, pp 3–18.

Read related articles

Taking the long livestock view, 23 Jan 2013

Greening the livestock sector, 22 Jan 2013

Livestock livelihoods for the poor: Beyond meat, milk and eggs, 8 Jan 2013

A fine balancing act will be needed for livestock development in a changing world, 7 Dec 2012

Fewer, better fed, animals good for the world’s climate and the world’s poor, 22 Nov 2012

Scientific assessments needed by a global livestock sector facing increasingly hard trade-offs, 12 Jul 2013.

A new global alliance for a safer, fairer and more sustainable livestock sector, 13 Apr 2012

Sharing the space: Seven livestock leaders speak out on a global agenda, 20 Mar 2012

Towards a more coherent narrative for the global livestock sector, 15 Mar 2012

Developing an enabling global livestock agenda for our lives, health and lands, 13 Mar 2012

Acknowledgements

This paper is an ILRI output of two CGIAR Research Programs: Livestock and Fish and Climate Change, Agriculture and Food Security.